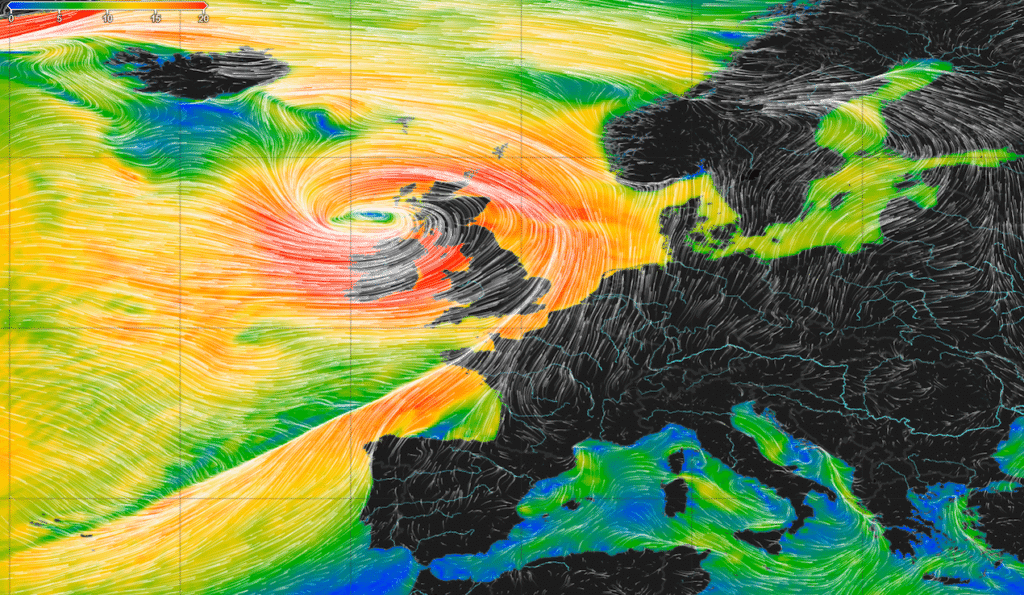

Storm Éowyn was a powerful extratropical cyclone in the 2024–25 European windstorm season, named by the UK Met Office on 21 January 2025 as forecasts highlighted a high-impact wind and rain event. It formed over the North Atlantic, rapidly deepened as it moved east and then struck Ireland, the Isle of Man, the UK and later Norway between 24 and 25 January 2025.

Meteorologists classified Éowyn as a very severe winter storm because its central pressure dropped from about 991 hPa to just over 940 hPa in around 24 hours, far exceeding the typical threshold for “bomb cyclone” rapid intensification. This explosive deepening created an exceptionally tight pressure gradient, driving destructive wind gusts that rivalled or broke existing national records.

Where and when it hit

Storm Éowyn’s main impact window was from the night of Thursday 23 January into Friday 24 January 2025, when the storm’s core crossed Ireland and then the UK. Ireland was hit first, followed by Northern Ireland, Wales, northern England and Scotland, before the system moved over the North Sea towards Norway later on 24–25 January.

National meteorological services issued the highest-level warnings ahead of the storm, including red alerts in parts of Ireland, Northern Ireland and central Scotland due to forecasts of hurricane-force gusts. These alerts covered key commuting hours, leading authorities to close schools, suspend many rail services and advise people not to travel in the most exposed areas.

Deaths and injuries

Authorities confirmed at least one death directly linked to Storm Éowyn when a man was killed after a tree fell on his car in County Donegal in northwest Ireland. Emergency services also reported multiple injuries across Ireland and the UK, mainly from falling trees, flying debris and traffic collisions in extremely hazardous driving conditions.

Health and emergency agencies warned that the true toll of the storm included indirect impacts such as people relying on generators, cold indoor temperatures during prolonged power cuts and dangerous journeys undertaken despite warnings. Hospitals and emergency rooms in affected regions activated severe-weather plans to cope with increased call-outs and difficult transport conditions.

Record-breaking winds and rainfall

Éowyn produced some of the strongest wind gusts ever recorded in Ireland, with a peak gust around 51 metres per second (about 114 mph) measured at Mace Head on the west coast, surpassing a previous national record from 1998. Across parts of Ireland, Northern Ireland, Wales and Scotland, widespread gusts above 80–90 mph (129–145 km/h) uprooted trees, tore off roofs and brought down power lines over a huge area.

In addition to extreme winds, the storm delivered bands of heavy rain and transient snow, especially in higher parts of Northern Ireland, northern England and Scotland, before quickly turning back to rain as milder air wrapped around the system. This mix of intense rainfall, snow and saturated ground increased the risk of localised flooding, landslides and further tree falls.

Power cuts: nearly a million in the dark

The most striking impact of Storm Éowyn was the scale of power outages, with estimates indicating that close to one million customers across Ireland and the UK lost electricity at some point during the storm. In Ireland alone, the state utility reported that more than 725,000–768,000 premises were cut off, roughly one-third of all homes, making it the worst storm ever experienced by the national electricity network.

In the UK, hundreds of thousands of homes across Northern Ireland, Wales and Scotland also suffered power cuts, with some communities remaining without supply for several days as engineers struggled to reach damaged lines in unsafe conditions. At the peak of the crisis, energy network operators said tens of thousands of people would not be reconnected until well into the following week because of the unprecedented level of damage.

Damage to infrastructure and nature

Power engineers reported that Storm Éowyn caused widespread damage to poles, transformers and overhead lines, frequently where trees had toppled onto the network under the force of the wind. Telecoms providers also experienced failures as mobile masts and fixed-line nodes lost mains power or were damaged by debris and falling trees, taking hundreds to thousands of sites offline.

Forestry and environmental agencies estimated that roughly twice as many trees fell during Storm Éowyn as would normally be felled in an entire year, transforming landscapes in some forests, parks and historic estates. Notable heritage properties such as Cragside in Northumberland reported extensive loss of mature trees and damage to grounds, drawing public attention to the storm’s ecological as well as human cost.

Transport and daily life disruption

Authorities in red warning areas shut all rail services in Scotland for the day of the main impact, while operators in northern England and north Wales told passengers to avoid non-essential travel. Many flights and ferry crossings were cancelled or delayed due to dangerous crosswinds and rough seas, especially on routes serving Ireland, the Irish Sea and the North Atlantic.

Roads across Ireland and the UK were blocked by fallen trees, power lines and debris, leaving some communities temporarily isolated. Major supermarket chains and businesses closed stores in the most affected regions, and widespread school closures meant many families stayed at home as the storm passed.

Recovery and restoration efforts

Energy companies launched large-scale repair operations immediately after the storm, bringing in additional crews and specialist equipment to replace poles, restring lines and clear vegetation from the network. Within a few days, operators reported that over 80–90% of affected customers had been reconnected, though tens of thousands in rural or heavily damaged areas waited far longer.

Telecoms firms worked in parallel to restore mobile and broadband services, often relying on generators, battery backups and temporary microwave links where fibre cables were severed. Local councils and volunteer organisations opened emergency centres, offered hot food and charging facilities, and checked on vulnerable residents who had been without light, heat or communications for days.

1 Comment

Pingback: Roy Keane the manager Man Utd never tried